Post by ᴍᴀɪᴢᴇ on Feb 23, 2018 0:50:01 GMT -6

Hunting

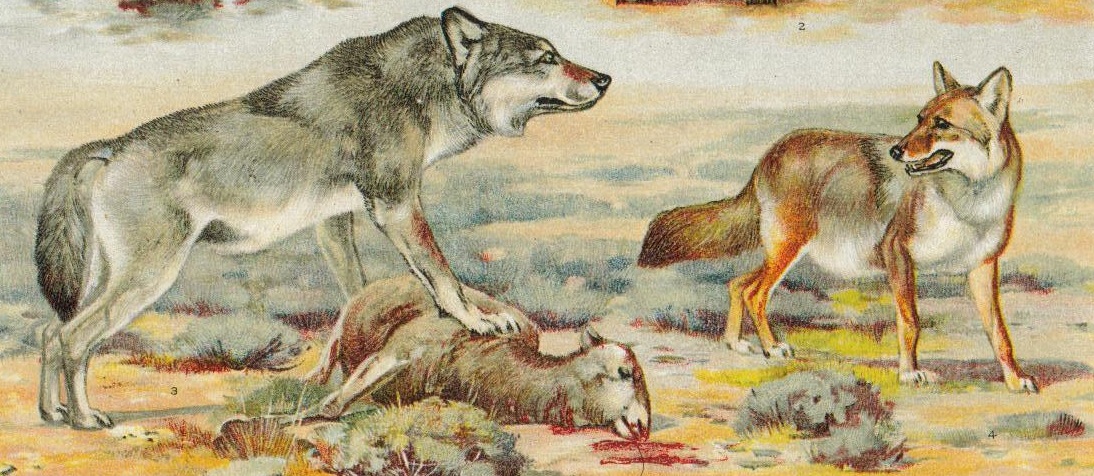

It is during a hunt where cooperation between wolves within a pack is most apparent. A wolf pack may trail a herd of elk, caribou, or other large prey for days before making its move. During this time, they are already hunting; they're assessing the herd, looking for an animal that displays any sign of weakness. This is just the beginning. Wolves must also factor in other conditions that will affect the hunt; weather and terrain can tip the scales in favor of predator or prey. (For example, a wide-open plain favors the ungulates, who, if full-grown and healthy, can outrun the fastest wolf. On the other hand, crusty snow or ice favors the wolves whose wide round paws have evolved to perform like snowshoes and carry them effortlessly over the surface. An experienced wolf is well aware that hoofed animals break through the crust and can become bogged down in deep snow.)

A wolf pack, therefore, weighs many different factors when selecting its target and, as circumstances change during the hunt, the target may change as well. (Initially they may be pursuing a calf, but if a big healthy bull stumbles unexpectedly, they all know to go after the bigger meal.) Conversely, if too many factors seem to favor the prey, they may choose to wait. Sometimes it is better to stay a bit hungry until the odds improve rather than expend precious energy on a fruitless chase.

Often fewer than half of wolves on a hunt are actually involved with physically bringing down the prey. The youngest wolves frequently do nothing more than observe and learn from the sidelines. Each of the other pack members contributes according to its particular experience and ability. Speedy, lightly built females often take on herding roles, darting back and forth in front of prey, causing confusion and preventing escape. Slower but more powerful males are able to take down a large animal more aggressively and quickly.

Wolves are not equipped to dispatch their victims quickly; prey usually dies of shock, muscle damage, or blood loss. If they can, one of the stronger wolves will seize the prey by the nose and hold on tight, helping to bring about a more expeditious end, but the animal can still take many minutes before it succumbs.

It is not rare for a wolf to be seriously injured by flailing hooves and slashing antlers. (Death could later take place if so.) A well-placed kick could break a wolf’s jaw, rendering it unable to feed itself. It is much safer to harass the prey and let it tire out before moving in close.

Although the alpha is usually in the thick of the hunt, it would be an exaggeration to say that they are leading it. The alpha may select the animal to be pursued, or they may choose to break off the hunt if it is going poorly. But they are not barking out orders to their subordinates like a general on the battlefield. The wolves just seem to know what to do, and they do it as one.

[source]

It is during a hunt where cooperation between wolves within a pack is most apparent. A wolf pack may trail a herd of elk, caribou, or other large prey for days before making its move. During this time, they are already hunting; they're assessing the herd, looking for an animal that displays any sign of weakness. This is just the beginning. Wolves must also factor in other conditions that will affect the hunt; weather and terrain can tip the scales in favor of predator or prey. (For example, a wide-open plain favors the ungulates, who, if full-grown and healthy, can outrun the fastest wolf. On the other hand, crusty snow or ice favors the wolves whose wide round paws have evolved to perform like snowshoes and carry them effortlessly over the surface. An experienced wolf is well aware that hoofed animals break through the crust and can become bogged down in deep snow.)

A wolf pack, therefore, weighs many different factors when selecting its target and, as circumstances change during the hunt, the target may change as well. (Initially they may be pursuing a calf, but if a big healthy bull stumbles unexpectedly, they all know to go after the bigger meal.) Conversely, if too many factors seem to favor the prey, they may choose to wait. Sometimes it is better to stay a bit hungry until the odds improve rather than expend precious energy on a fruitless chase.

Often fewer than half of wolves on a hunt are actually involved with physically bringing down the prey. The youngest wolves frequently do nothing more than observe and learn from the sidelines. Each of the other pack members contributes according to its particular experience and ability. Speedy, lightly built females often take on herding roles, darting back and forth in front of prey, causing confusion and preventing escape. Slower but more powerful males are able to take down a large animal more aggressively and quickly.

Wolves are not equipped to dispatch their victims quickly; prey usually dies of shock, muscle damage, or blood loss. If they can, one of the stronger wolves will seize the prey by the nose and hold on tight, helping to bring about a more expeditious end, but the animal can still take many minutes before it succumbs.

It is not rare for a wolf to be seriously injured by flailing hooves and slashing antlers. (Death could later take place if so.) A well-placed kick could break a wolf’s jaw, rendering it unable to feed itself. It is much safer to harass the prey and let it tire out before moving in close.

Although the alpha is usually in the thick of the hunt, it would be an exaggeration to say that they are leading it. The alpha may select the animal to be pursued, or they may choose to break off the hunt if it is going poorly. But they are not barking out orders to their subordinates like a general on the battlefield. The wolves just seem to know what to do, and they do it as one.

[source]

(<cougar cubs)

(<cougar cubs)